![]()

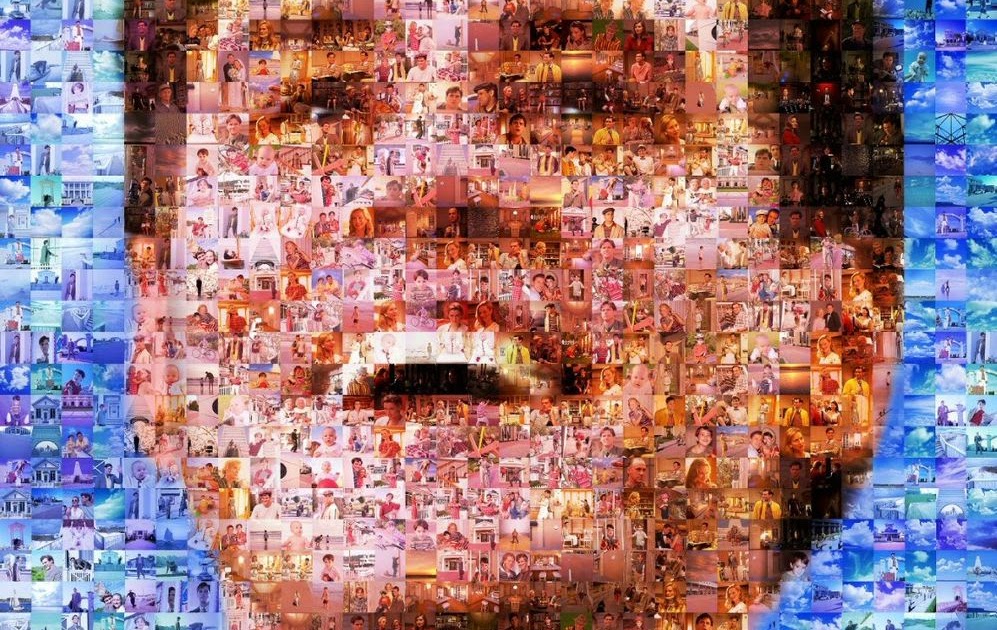

The Truman Show (1998) Directed by Peter Weir

The sobering statement against modern society’s voyeuristic mania for celebrity culture eloquently articulated in the existentialist dramedy The Truman Show seen in the twilight of the 20th century when it premiered was like witnessing a powerful techno pop prophecy about the toxic relationship we have with reality and fiction. Today, its prophetic force feels rather trite and dated. To my mind, The Truman Show remains a relevant piece of American cinema for its collateral effects, which somehow derive from its incisive commentary against the frivolities associated with reality television.

When the too-perfect-to-be-real Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey) begins to question his plastic reality, the existentialist crisis that engulfs him announces itself to be more than just a sharp anti-television culture breakdown of the unsolicited collusion that exists between ordinary audiences and industry bureaucrats to normalize the violation of celebrity privacy. With this in mind, it is simply impossible not to notice that the critique is more holistic than it seems, leaving open the possibility that it is also a statement against the dangers of the medium, not of television but of cinema. Metaphor or not, there is no doubt that this major film directed by Peter Weir and written by Andrew Niccol has a lot to tell us about the medium and the capacity it has to make reality and fiction inextricable in a corrosive and perilous fashion. Truman Burbank is an idyllic character at first, living in a utopia created by the meticulous demiurge (Ed Harris) of the 24-hour live worldwide television program called The Truman Show. More than a character structured to the rules of a conservative society, there is something special in his innocent spirit that makes him extraordinary in the most heterodox sense of the word; gradually his sympathy becomes synonymous with torture – though the story is never biting or even aggressive in dealing with the maelstrom of emotions Truman goes through, the inhuman context of his existence and the systematic falsity in which his identity is constructed make the film a painful nightmare – the visceral device of Andrew Niccol’s inventive narrative structure is to portray Truman as a sympathetic figure of speech who ultimately turns out to be a helpless victim.

Truman’s apocryphal life is seen as that of an automaton being coordinated to the liking of its creators; he has lived since birth in a gigantic stage where television directors and scriptwriters have written and prepared his life to be seen live by the real world. The victim factor appears as soon as we realize that Truman’s existence is rendered meaningless by the fact that he is in a certain way dead in life. His parents, his wife, his best friend and even things as subjective as his fears are fake. In that studio – designed to look like a city on an island – where Truman lives there are thousands of hidden cameras and extra actors manipulating the life of a human being for the sake of entertainment. The concept is bone-chilling just thinking about it, although it all unfolds in a peaceful atmosphere, the conceptual power of the script unsettles you when you ponder it the most. Jim Carrey’s shockingly dramatic performance makes the story all the more compelling, especially when his trademark comedic delirium is optimally harnessed to translate the situational and emotional perplexity in which Truman finds himself.

To be born, grow up and reach adulthood only to learn that your whole life was a gross lie is the film’s tragic edge; the melancholy, obfuscation and profuse dread that Truman displays are a poignant deconstruction of cinema that urgently captures our attention. It is an academic platitude to study fiction and its mimetic nature to evoke reality, but the almost didactic urgency of The Truman Show to dissect the moral concerns surrounding the nature of filmmaking is so intimate and heartfelt, that peering through the surreptitious cameras that portray Truman’s life becomes for the first time a conscious act in which the audience questions their role as viewers. Even after so many years this film is still capable of reshaping the philosophy of cinema, and that is what ultimately establishes it as one of the most thought-provoking American films of all time.