![]()

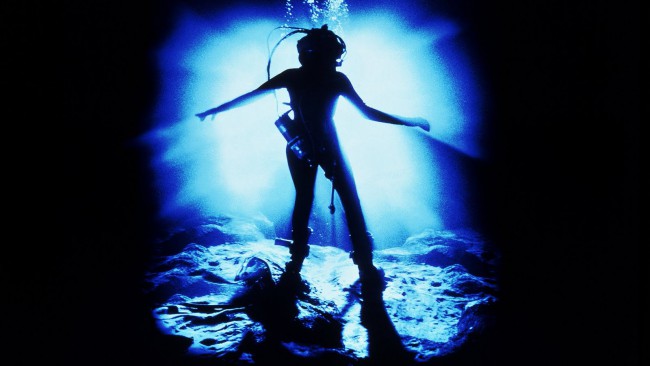

The Abyss (1989) Directed by James Cameron

*This review is about the Special Edition of the film, also called the Extended Cut.

George Lucas may have shaped today’s concept of blockbuster filmmaking with Star Wars, Steven Spielberg may have redefined the medium with his popcorn operas, but James Cameron made it art. After crafting two of the most influential action pictures of all time in 1984 and 1986, the ambitious fellow came along in 1989 with one of the most intrepid film projects – chimerical to the incredulous, conceivable to the believers – ever undertaken in a studio production. James Cameron’s aquatic Blockbuster monolith is the work of a madman, of an egomaniac filmmaker willing to materialize his visions on celluloid at the expense of his own and his crew’s safety. Much has been commented on the arduous shooting conditions to which the entire film crew was subjected just to satisfy the caprices of a visionary, the harsh and rigorous treatment of the director to his cast has been criticized, and the danger and the physical and psychological pressure to which all were immersed during the filming has been denounced. By now, the whole story behind the demanding shooting of The Abyss is in itself a myth in the history of modern cinema. The unfilmable was filmed and thank God for it! Because the extreme self-sacrifice of each and every member of this maniacal production to pull off this quasi-utopian endeavor was worth it, they made history, and gave us one of the most haunting, transcendental underwater cinematic adventures ever made.

At first, James Cameron’s The Abyss is a paraphrastic rip-off of Ridley Scott’s Alien and its sequel Aliens directed by Cameron himself, but then when all the extraterrestrial pomp and glittering special effects showmanship take transcendence in the plot Cameron’s cinematic paraphrasing of other Blockbuster classics gets focused and aligned towards another of the all-time greats, Steven Spielberg’s seminal poetic masterpiece Close Encounters of the Third Kind. While this may seem an intrinsic blemish on James Cameron’s trademark commercial moviemaking, in The Abyss it is not. These over-the-top inspirations may feel like shortcomings that undermine the credibility of Cameron’s genuine craftsmanship, but when you consider it thoughtfully you realize that the rhetorical and clichéd narrative system that The Abyss employs is that of a universal one. There is no such thing as a Blockbuster motion picture that hasn’t borrowed certain storytelling mechanics from other films. That’s what big-budget filmmaking is all about as it seeks to elicit the most thrilling, knee-jerk responses from its audience who come to the movies for a sensory experience, not an intellectual one. The system created by the triumvirate of American populist cinema -Spielberg, Cameron and Lucas- is inescapable, it is hegemonic. The Abyss does not purport to be an adventure yarn you’ve never seen in the movies, it purports to be more of the same but with an unparalleled technical twist, which ultimately turns The Abyss into one of the best paragons of modern American cinema. Sure, the story that unfolds in The Abyss is nothing groundbreaking, but have you ever seen such clichés work so beautifully within one of the most innovative settings of all time? I’m sure you haven’t, or at least I can speak for myself, because I’ve never been viscerally assaulted with so many rhetorical sequences functioning as if I’ve never seen them on film before.

It is clear to me that James Cameron was not concocting the idea and overall story of The Abyss from a narratological blueprint, but rather he was engineering its structure from the very beginning of his flourishing career from a technological blueprint. He invested all his time not in designing a plot but in how to pull it off with cutting-edge technicalities that would eventually make The Abyss a technical tour de force. James Cameron’s claustrophobic, underwater escapade is first and foremost an enormous, unprecedented milestone in motion picture engineering. The painstaking logistics behind the terror, poignancy and exhilaration in The Abyss is a cinematic masterstroke that should be acknowledged for what it is, a mad, life-threatening act of love for cinema and the business of entertainment.

I guess the best way to describe the overwhelming pathos of The Abyss would be to take the commendable individual descriptions given to Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and render them collectively. Something like this, Close Encounters of the Third Kind: An Aquatic Odyssey. Mentioning Spielberg’s film needs no explanation, but Kubrick’s? I will elaborate on a response to that in a moment. The storyline of The Abyss is infallible, the U.S. government sends a SEAL team to the Deep Core – an underwater drilling platform – to use it as a base of operations to determine what happened to the sinking of an American submarine after it encountered a USO – an unidentified submerged object. The Deep Core team led by Virgil “Bud” Brigman (Ed Harris) is initially skeptical of the mission, as Bud’s team is not trained for this type of military operation; however, he and his team take on the responsibility of hosting the unfriendly, unromantic SEAL team on orders from the U.S. government. The SEAL team is commanded by Lieutenant Hiram Coffey (superbly played by Michael Biehn who played the hero in Cameron’s The Terminator and now ironically plays the villain), but the team comes with a surprise. Dr. Lindsey Brigman (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) joins them, the designer of Deep Core’s experimental, mammoth underwater platform, who also happens to be Bud’s estranged wife. With this pragmatic framework alone, Cameron has everything in place to plunge us into the dark blue depths of the ocean and leave us there for a few long, if imperceptible, epic hours. So be sure to bring plenty of oxygen with you because you’ll need it. Everything that is not supposed to go wrong in the mission, goes awry.

For starters, a storm is brewing, which complicates the operation they must carry out, and the motivations of the American government differ from those of the Deep Core team; the morale of the SEAL team is unaccountable, they just follow orders no matter how harebrained they may be, Bud’s team are the only ones with a rational ethic. So, it doesn’t take long for the incompatible agendas to start colliding and sparking squabbles that lead to nothing but tragedy. The plot turns into a sea juggernaut when the characters and we realize the level of peril they are in, and in the depths of the ocean no less, where there’s not much you can do! But in all the ever-present tense energy that the film exudes, miracles transpire. Humongous, translucent, shape-shifting, unidentified creatures appear in the midst of the chaos of survival. These creatures are harmless but have the omnipotence to control the waters of the earth and cause catastrophes of biblical proportions if provoked. Dr. Brigman is one of the first to witness the majesty of these extraterrestrial creatures and is so mesmerized by them that she takes photographs of them to show the rest of the crew. But Lieutenant Coffey’s warmongering paranoia keeps him from seeing reality – the heritage of McCarthyism is still so prevalent and the Cold War preconceptions so latent that this character embodies the worst of the American government during the Cold War – he refuses to believe that aliens were responsible for the sinking of the submarine, for him it was the Russians. In the same manner as the Cuban missile crisis, the underwater operation goes from being a mere threatening bellicose speculation to a serious possibility of the eruption of a third world war. Amid The Abyss’ anti-militaristic, anti-nuclear and pro-environmentalist commentary, the plot leaves rewarding room for character development that works as well in its metaphors of the metaphysics of love as it does in its operatic dramatics.

The profound performances of Mastrantonio and Ed Harris as the married couple going through an incendiary divorce are the soul of the film at its most humane. The two are a battle of egos and the consummate epitome of a love-hate relationship, in which love ultimately triumphs. Mastrantonio’s Dr. Brigman is a brave and intelligent woman, but her tough intellect sometimes reveals her insecurities making her a character with a seemingly resilient nature but one that hides her sensitivities. Ed Harris’ Bud Brigman is very similar to her, they are a match made in heaven, although the only difference is that he is less prideful and more self-assured in voicing his feelings. Cameron’s script gives them a past – that of being in love – and gives them a present – that of a married couple fighting and on the verge of divorce – but it also gives them a future – that of reconciliation – but this does not occur in a prosaic manner, but in a poetic one. For it is the tragic circumstances that lead them to reassess their feelings for each other. Both learn that they cannot live without each other; this monumentalizes the notion of marriage in its most metaphysical manifestation. Witnessing the two of them forge a bond of love that was once tenuous is one of the most touching romantic tales set in the midst of a nail-biting, claustrophobic underwater affair. The film teaches you that it is in the hard times that true love is experienced at its most convoluted expression, not in the idyllic stages.

James Cameron’s over-the-top romantic prose layered in mind-blowing underwater imagery courtesy of Mikael Salomon never hides that its ultimate goal is to impart an eye-opening message. Even though the bona fide intention of his message is sheer truism, and not all that persuasive, the picture is so miraculous that you do your best to believe in it. However, for my humble judgment, the message itself is not what I like most about the film in the most literal sense of the concept. What I appreciate most about The Abyss is its puerile optimism. Believing that someday humans will stop killing each other and that wars will disappear is an elusive utopia. But I love believing that it could be possible even if I know deep down inside that it is not. The film holds that feeling in its heart as a brave warrior fights for his ideals.

The magnificent aliens of The Abyss forgive the human species. As Cameron would do in his other stupendous 1991 Blockbuster Terminator 2, Cameron pursues the idea that if his fictional creatures/machines can learn to forgive, love and spread peace, why can’t we? Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey has certain paradoxical sentiments, and these are those of misanthropy and humanism. At times one might think that The Abyss is also a film that exhibits a certain misanthropy, but in the end the hopes for the prosperity of the human species overrides any trace of pessimism. The merciful aquatic aliens show Bud the barbarities that the human species has committed against itself and nature since immemorial times, but Bud teaches the aliens with his act of love for his wife that there will always be hope as long as the good ones exist. James Cameron’s rewarding humanistic philosophy offers a second chance, just as Kubrick does in his cold, monumental masterpiece. When we finally – after having been underwater for asphyxiating hours – rise to the surface to the rhythm of Alan Silvestri’s awe-inspiring score in the operatic, ridiculously beautiful apotheosis of The Abyss, we recognize the artifice of the moment even in our suspended disbelief, but we embrace it because like Cameron, we give ourselves a second chance to be better humans. That’s precisely the feeling a great film of this sort should leave you with.