Directed by Archie Mayo

Written by J. Grubb Alexander

Starring:

- John Barrymore as Svengali

- Marian Marsh as Trilby O’Farrell

- Donald Crisp as The Laird

- Bramwell Fletcher as Billee

Rating: ![]()

As a pre-Code potboiler steeped in obsession, erotic melancholy, and hypnotic mind-games, Svengali is a dark delight—morally twisted, visually stylized, and just unhinged enough to make it sing. But as an adaptation of George du Maurier’s beloved Trilby, it’s lopsided at best, borderline hijacked at worst. The novel told a story of a young woman’s rise and fall; this film mostly wants to show off the man who pulls her strings.

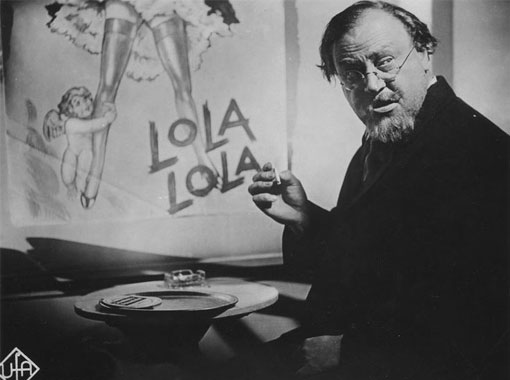

And what a man—if you can call him that. John Barrymore sinks his fangs into the role of Svengali, the spectral music tutor with lank hair, haunted eyes, and an ego the size of a cathedral. He’s like Nosferatu moonlighting as a voice coach. This isn’t love—it’s hunger. Svengali sees Trilby, hears her voice, and decides she’s his to mold, possess, and parade. Her consent is optional.

Enter Marian Marsh, seventeen, radiant, and heartbreakingly raw. As Trilby, she plays the part of the naïve model with a golden voice and a fragile heart. In her earliest scenes, she’s all playfulness and charm, a sunbeam in a gloomy Paris. But as Svengali wraps his psychic coils around her, that light dims. Marsh captures every shade of her character’s descent—from wide-eyed warmth to ghostly vacancy. She even gets a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it pre-Code moment of near-nudity, framed tastefully in soft lighting, more Botticelli than scandal rag. It’s not played for titillation, but rather as a moment of liberated beauty and trust, marking both her character’s artistic spirit and Marsh’s own fearless presence on screen.

That’s the film’s fatal flaw. It’s called Trilby, not Svengali, yet the spotlight clings to him like a curse. The emotional core—Trilby’s loss of agency, her fractured identity—is undercut by the film’s infatuation with its villain. Instead of exploring her interior life, we’re treated to Barrymore’s hypnotic monologues and wild-eyed gesturing. He’s a one-man sideshow, stealing every scene and leaving the real tragedy in the shadows.

To Barrymore’s credit, he’s unforgettable. His Svengali is theatrical to the point of madness—a walking opera of twisted ego, spooky charisma, and ghoulish flair. He belongs in the Universal horror stable, right next to Dracula and the Phantom of the Opera. His performance walks a high wire between comedy and terror, but never loses its grip. It’s camp, it’s creepy, and it works.

The rest of the film, sadly, can’t keep up. Director Archie Mayo seems unsure whether he’s helming a gothic tragedy or a supernatural melodrama. The tone lurches, the pacing stutters, and the script leaves plot holes large enough to fall through. There’s talk of art, autonomy, and spiritual possession, but it’s all smoke and no fire. The literary depth of du Maurier’s novel is mostly abandoned in favor of lurid spectacle and theatrical excess.

Still, Svengali has something—a weird magic that refuses to be dismissed. Beneath its uneven direction and misplaced focus lies a story of disturbing power: a man obsessed with beauty, and a woman stripped of her voice, then turned into someone else’s masterpiece. It’s a psychosexual ghost story, a pre-Code fever dream where control masquerades as love and charisma cloaks cruelty. Even when it misfires, it fascinates.

So no, it may not be a faithful Trilby, but as a gothic-pulp tale of obsession and stolen identity, it’s strangely hypnotic. A film less about music than manipulation, less about love than domination. It’s cracked, cruel, and kind of magnificent.