Evocations and Premonitions in Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel

-Lola Lola: What do you want?

-Prof. Immanuel Rath: I’m here on official business. You’re corrupting my pupils.

-Lola Lola: Really? Think I’m running a kindergarten? [Begins undressing.]

-Lola Lola: What’s wrong, cat got your tongue?

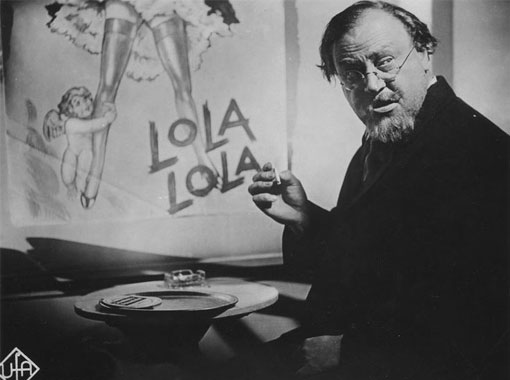

If there is one film from the Weimar Republic that accurately illustrates the socio-political morale of the German people in the early 1930s and forecasts the alarming popular ascendancy of National Socialism and its eventual triumph, it is Josef von Sternberg’s deliriously sensuous 1930 masterpiece The Blue Angel. It was the German film industry’s first foray into the fledgling new sound medium; for the Austrian director it was his second sound film – erroneously believed to be his first sound film when in fact that was Thunderbolt made in 1929. Still, this film is a landmark for having many first-time events. It was the beginning of the legendary collaboration of Marlene Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg that would last for many years to come and catapult the multi-talented German actress and singer to Hollywood stardom. This production was also the first time Dietrich had a leading role. Another curious fact is that this was the first and only German film that Sternberg directed. Now leaving aside the historiographical curiosities, let’s return to the transcendent aspects that make this film a canonical work in world cinema. Today popular culture remembers Dietrich’s sublime melodious voice singing memorable songs like “Falling in Love Again (Can’t Help It)” and “They Call Me Naughty Lola” more than the chilling descent into madness of Professor Immanuel Rath played by the great Emil Jannings; or perhaps they recall more the lascivious imagery of Dietrich exhibiting her carnal attributes than the sumptuous aesthetics of the mise-en-scène orchestrated by Sternberg. It is even more than certain that many moviegoers have been introduced to this film thanks to the unsettling performance of Helmut Berger, who appears cross-dressed as Marlene Dietrich in Luchino Visconti’s The Damned. Or maybe you know this film from the reference in Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, where Louis Garrel jerks off looking at Marlene Dietrich’s photo in The Blue Angel. Be that as it may, The Blue Angel is one of those rare, unusual occurrences where a German art film from the 1930s is remembered even by people who haven’t even seen it.

Certainly, the enduring power of Sternberg’s film lies in its sociocultural relevance, yet its sociopolitical incitements are even more meaningful, even on a cinematic scale. The story of The Blue Angel is based on the 1905 book by Heinrich Mann – Heinrich was a brilliant German writer renowned for his trenchant criticism of Nazism and the burgeoning fascism that beguiled almost all of Europe at the time – one could say that the thematic corpus of the literary opus is that of an anti-bourgeois diatribe with burlesque overtones. In short, it is a social critique. But Sternberg, who has always been characterized as anything but a conformist, broadened the book’s thematic spectrum and added multiple other things – from exaggerating Professor Rath’s tragedy to altering the ending entirely – these impulsive creative modifications gave the adaptation an authentic quality to dissect the socio-political context of the Weimar Republic. Consequently, The Blue Angel is consistent in addressing issues of the utmost importance for the time in which it was made. This is mere speculation, but it seems that somehow Sternberg sensed that returning to his beloved native Vienna would be impossible in the future for obvious reasons – Sternberg was the son of orthodox Jews – thus his first and last German film represents a kind of political statement by Sternberg against what was happening at the time. The great irony here is that this film was produced by the German television and film company UFA, which was directed by Alfred Hugenberg, who was one of the major supporters of the Nazi party and the infamous extremist policies of nationalism and who later became minister of economics and agriculture in Adolf Hitler’s first cabinet in 1933. Clearly, Hugenberg was literate in politics but not in film, as he naively gave the budget to direct a film that turns out to be an incisive exposé of the nefarious Nazi demogogy. The film was scheduled to premiere in Berlin on April 1, 1930, but the UFA canceled its release as a censorship measure because Hugenberg had just learned that the story of The Blue Angel was linked to the socialist writer Heinrich Mann. Despite the truncated German release of the film, the film’s international release was a success. Americans adored Dietrich, critics lauded Sternberg’s flamboyant style, and everyone admired Jannings’ superb performance.

Josef von Sternberg helmed what was arguably the first and most ambitious European sound film in the history of cinema. Anyone familiar with Sternberg’s eccentric personality and many biographical aspects about him will know that Sternberg was never a sound enthusiast. He was a staunch purist of the cinematic image, and as such always defended the use of image over sound as a method of filmmaking. His uncompromising formalism motivated him to embrace sound experimentally; when we watch The Blue Angel the sound is peripheral, the mise-en-scène and the pictorial language of the framing are what tell the story, not the sound. The sound in Sternberg’s film is more musical – in theory this is Sternberg’s first musical film – when Marlene Dietrich sings is where the sound takes preeminence, however the visual compositions lead the music not the other way around. Almost all the early sound films, American and European, suffered from the primitivism of utilizing the sound shooting system – there were two, sound on disc and sound on film, the latter would be the best and the one that would be settled forever in the industry – evidently, The Blue Angel was no exception, there is a static languor in many sequences that indicates a linguistic regression in the art of cinema. However, Sternberg harnesses these shortcomings like a master with enough experience and flair to camouflage them with a sensuously expressionistic mise-en-scène. The visuals that Sternberg concocts with the magnificent cinematographer Günther Rittau are exquisitely contemplative. Basically, these aesthetic features lend an enormous sophistication to the visual storytelling while acknowledging the unavoidable flaws that emerge due to the primitive techniques of the sound medium. There comes a point in the film when you feel like you are watching a silent film rather than a sound film, which may be one of the reasons why Sternberg’s film looks so gloriously distinct from other sound films made in the same year. But beyond the technical elegance of Sternberg’s visual approach, I believe that the evocation of watching a silent film comes more from the unmistakably physical performances of Dietrich and Jannings. Both preferred gestures as a means of language over dialogue – rumor has it that Sternberg himself eliminated a great deal of dialogue in the script – and that predilection for dramatic physicality comes through in every scene. Consequently, they are performances of silent cinema, not talkies. And this provides the film with an aura of inimitable artistic expression. In the end Sternberg’s experimentation with sound in this film in my judgment turned out to be more than successful, it was groundbreaking.

The memorable plot may sound trite today, but trust me, for the morality of Europe’s tumultuous 1930s, the thought-provoking plot of The Blue Angel was scandalous. It is part erotic drama, part political satire and part tragic horror, all tonalities that come together to articulate one of the most corrosive depictions of the decadence of the Weimar Republic. In a nutshell, it is the story of a strict professor (Emil Jennings) with puritanical principles who falls madly, and dangerously, in love with a captivating cabaret singer named Lola Lola (Marlene Dietrich). The verisimilitude of this narrative structure is found in the naturalistic interaction of the plot with the scenery and expressionistic performances. Sternberg with his consistently meticulous staging gives us hints of how his characters will behave and how their conflicting personalities will gradually develop into a gripping tragedy. At the beginning when we meet the stout and square Professor Immanuel Rath we see in him the embodiment of the post-war resentment that contaminated German society with hatred and prejudice. Emil Jannings with striking poses and authoritarian bravado shows Immanuel Rath as a burlesque version of the German middle-class intellectual, his students are rebellious and ill-mannered youngsters who rejoice in making fun of the lonely and dull Professor Rath. However, the jokes never reach the point of humiliation; Immanuel Rath represents an academic authority and therefore knows who he is and has a well-inflated ego. But this all changes when Rath, scandalized to learn that his students go to a cabaret every night to see the sensual Lola Lola, ends up meeting this mesmerizing woman who challenges his conservative values. Dietrich is simply phenomenal in the role of Lola Lola, she is unabashedly libidinous and aptly vulgar. When the two characters meet, this is when the film begins to play malevolently with Immanuel Rath’s psyche. This character has a typically German pride, but little by little this pride diminishes and he ends up denigrated. Witnessing the character in a demoralized state is one of the most terrifying things I have ever seen. The psychological and physical transformation he undergoes when he falls into the thrall of Lola Lola’s intoxicating beauty makes him forget his dignity as a human being. But there is something else to highlight in the plot that I consider interesting, and that is that apart from Dietrich and Jannings playing the two protagonists, there is another protagonist who does not appear individually but collectively, and they are the young students of Professor Rath. They relish the miserable and schizophrenic state of their professor, rejoicing in humiliating him once they have lost all sense of respect for him. The irreverent ideals that these teenagers embrace do nothing but evoke the Nazi cruelty and nationalistic misanthropy that poisoned all the youth of those times, the so-called Hitler youth. There is something psychopathic and inhuman in seeing how a human being can sadistically enjoy the absolute perdition of another human being. They encapsulate that frighteningly well.

But to talk about The Blue Angel and not mention anything about its horny eroticism is like discussing about Hitchcock and not mentioning suspense. The Blue Angel is undoubtedly the most erotic film Sternberg ever ventured to make – though his last exotic 1953 masterpiece Anatahan is another good contender, his 1930 film has Dietrich in it, and there’s nothing more sizzling than watching Sternberg direct his fetish actress. To paraphrase the latter, it’s not that Dietrich exclusively is the reason for the extreme sensuality displayed in this film, it’s rather how Sternberg films his muse. In several sequences Dietrich exhibits extra flesh, but it is not simply the gratuitous exhibition of Dietrich’s body that makes the sexual erotic, it is Sternberg’s lubricious fascination with the protruding framing of her legs in pantyhose. The camera angles are persistently suggestive, nothing in the mise-en-scène can overshadow Dietrich’s smooth legs, which always have to be in an inviting position for the photographic composition. Not even Jennings’ plump anatomy is capable of drawing more attention than Dietrich’s shapely thighs. Sternberg being one of cinema’s great stylists (if not the best) was a stickler for detail to best portray his actresses, particularly Dietrich. One can feel a kind of reverence for her that when analyzed can feel more like an obsession. Who knows, it is very likely that Sternberg identified with the professor’s infatuation with Lola Lola in the same way that in real life the director idealized the female figure of Dietrich. There is an indelible moment in the film that could be my candidate scene for the most stylishly obscene thing Sternberg did in his career. This scene is of Professor Rath on his knees putting on Lola Lola’s pantyhose. It is she who instructs him with a domineering candor to put on her pantyhose, he does everything she tells him no matter how ridiculous the quasi-masochistic relationship appears. The composition of this scene is titillating, the actors are positioned in the most provocative fashion possible; Sternberg wants Dietrich’s glistening legs to be seen in their maximum splendor but at the same time he wants us to observe Jannings’ submissiveness. It is an enticing and even exploitative dynamic I would suggest, but it is profoundly lustful and instrumental in rendering the story a psycho-sexual journey as well.

Watching The Blue Angel is an enthralling exercise in which new things are discovered the deeper you delve into the visual textures of its frames. It stimulates a diversity of themes ranging from the political to the social, but above all it is pure cinema experimenting with the impurities of the sound medium; it is far from feeling modern in the most cinematic sense of the word, but its haunting effects are still intact and its predictions at the time proved chillingly accurate. I’m not too comfortable with claiming that this is Josef von Sternberg’s finest film, but I do feel confident in claiming that it is the most essential film in his immaculate career. With all due respect to Fritz Lang’s M, in many respects, this is the magnum opus of the Weimar Republic.