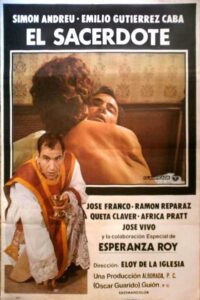

Directed by Eloy de la Iglesia

Written by Enrique Barreiro

Starring:

- Simón Andreu as Father Miguel

- Emilio Gutiérrez Caba as Father Luis

- Esperanza Roy as Irene

- José Franco as Father Alfonso

- Ramón Repáraz as Father Manuel

Rating: ![]()

Eloy de la Iglesia takes a stab at Buñuelian iconoclasm, capitalizing on the removal of censorship in post-Francoist cinema to indulge in a style of anticlerical burlesque at its most extreme as political satire and sexual commentary looking back on 1960’s Spain. In 1977, Spanish cinema’s most transgressive gay Marxist proved he was already basking in the cinematic liberties that came in the wake of the lurid S-rated cinema when he dealt with the taboo-defying bestiality in yet another of his masterful caustic commentaries on Spanish society, the revoltingly erotic canine masterwork The Creature. If the exploitation weirdness seen in The Creature is your cup of tea and if the grimy slasher allegories of Eloy’s video nasty Cannibal Man worked wonders for you, then The Priest will appeal to you as the wet dream of all Eloy de la Iglesia’s aficionados. Add to this satirical fare the enlightened sexual expression of El Diputado and Los Placeres Ocultos and voilà, you get what is arguably the quintessential film from the controversial Spaniard cineaste.

Eloy de la Iglesia takes a stab at Buñuelian iconoclasm, capitalizing on the removal of censorship in post-Francoist cinema to indulge in a style of anticlerical burlesque at its most extreme as political satire and sexual commentary looking back on 1960’s Spain. In 1977, Spanish cinema’s most transgressive gay Marxist proved he was already basking in the cinematic liberties that came in the wake of the lurid S-rated cinema when he dealt with the taboo-defying bestiality in yet another of his masterful caustic commentaries on Spanish society, the revoltingly erotic canine masterwork The Creature. If the exploitation weirdness seen in The Creature is your cup of tea and if the grimy slasher allegories of Eloy’s video nasty Cannibal Man worked wonders for you, then The Priest will appeal to you as the wet dream of all Eloy de la Iglesia’s aficionados. Add to this satirical fare the enlightened sexual expression of El Diputado and Los Placeres Ocultos and voilà, you get what is arguably the quintessential film from the controversial Spaniard cineaste.

While having the fundamentals of Eloy’s cinema, The Priest is a piece of oddity; very idiosyncratic given that it is a period film set in 1966, specifically during the Spanish Referendum on the Organic Law of the State. Simon Andreu plays the titular priest in what promises to be a plot of mirthful smut. At first glance, Father Miguel (Andreu) fits neatly with the ideals that Christianity preaches to its adherents, he is a godly man in his mid 30’s, a bit shy and aloof, a virgin but inquisitive about his surroundings. Particularly curious about a married woman (Esperanza Roy), who goes to the confessional every now and then, rather than seeking the Lord’s mercy, it is an excuse to have an intimate conversation with her favorite priest. Miguel, despite his unwavering devotion to God, undergoes many revelations that call into question his faith and his status as a religious individual. Repeated epiphanies of the sacred is what every priest would expect during his ministerial life, yet Miguel only gets multiple epiphanies of the sexual kind. And these do not occur in any ordinary place but in the middle of mass right during the Eucharist. He has a wild imagination, his belated sexual awakening has voyeuristic tendencies, picturing many of the parishioners having sex. But that is only a taste of his sinful urges. Later on these turn into sexual depravity.

Miguel seems to be possessed by a pervert, or perhaps he is a pervert and doesn’t acknowledge it. Although the transgressions invariably allude to something earnestly socio-political, the boldness of Eloy de la Iglesia’s filmmaking never fails to be a necessarily tasteless assault on conservative decorum. Yet no matter how scathing the maximalism of depravity shown here, Simon Andreu’s thoughtful performance allows sufficient room for introspection and heartfelt empathy that every sacrilegious and immoral activity his character engages in serves as an instinctual response to the damaging sexual inhibition he experiences as a result of celibacy. The political commentary navigates the tormented feelings of our main character with the same artful rigor as the more vulgar bourgeois satires from his compatriot filmmaker Luis Bunuel. But these fulfill a purpose beyond the allure of simple exploitation, the sexual perversion plays more like a physical and spiritual turmoil engendered by institutional hypocrisy.

As with all of Eloy de la Iglesia’s output, The Priest is unafraid to be shocking for both the right and wrong reasons; and with a deft convergence of exploitative stylings and arthouse praxis, it shows Miguel’s kinky proclivities as straightforwardly as possible. His urges range from the innocuous desire to want to sleep with an adult woman to sexually desiring a little boy. And these degenerate drives are never stationary, they evolve in one way or another as an indication not necessarily of sexual discovery but of identity as a person who has been repressed for a long time. The ever-present homoeroticism as seen through Eloy’s lustful lens also plays a role in the plot, but that is only a small part of his many daydreams. What is actually more crucial to the plot is how Miguel reacts to these instinctive impulses. Self flagellation, severe penance and oppressive guilt are the only methods the church has taught Miguel to quell his craving for the flesh. But of course none of this works out as he would like it to, for this is all about a priest’s hopeless quest to calm his horniness. During one of the film’s most meditative bits – when Miguel visits his mother in his hometown – the story grows so intimate that the empathy, the rapport between character and audience, feels unavoidable. Eloy is the master of unprejudiced cinema, no matter how twisted his characters are, he truly believes in them as redeemable beings regardless of their monstrous sins. He has always considered himself an outsider, so it makes sense that he would reflect on the marginalized. Anyway, what happens at this stage in the plot is essential to fully grasp the caustic underpinnings of the political commentary on this character’s behavior. Miguel recalls his childhood during his visit. In his reminiscences we learn more about his life, his troubled relationship with his father, his friends and early sexual explorations. Besides staging one of the most graphic sequences of a bunch of naked kids raping a poor duck, Eloy de la Iglesia gives us the opportunity to further understand the priest’s tumultuous inner feelings.

It’s a challenging cinematic endeavor – what Eloy film isn’t? – but it serves its purpose in a fashion that I didn’t anticipate would move – and shock – me. It is exactly what I most want to get from one of the most radical directors in Spanish cinema, poignancy and exploitation-isms is the right match that every great Eloy film must have. And this one certainly contains it and much more than that. Crazy stuff even by the standards of Spanish films classified S, climaxing with what is the most outrageous act of celibacy that has ever been seen. In the satirical tone intended by Eloy I would suggest that it was the sickest feat of faith ever seen in cinema.