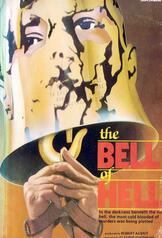

– Bell from Hell is the movie for the weekend. In this section every Saturday or Sunday Celluloid Dimension picks a movie for the weekend. The selections are preferably underrated movies or neglected movies that we think should get more attention. Have fun with these recommendations. –

Directed by Claudio Guerin

Written by Santiago Moncada

Starring:

- Renaud Verley as Juan

- Viveca Lindfors as Marta

- Alfredo Mayo as Don Pedro

- Maribel Martín as Esther

- Nuria Gimeno as Teresa

Rating: ![]()

Claudio Guerín’s Bell from Hell unfolds like fog over a place once visited in a dream—recognizable in shape, but foreign in feeling, until dread fully settles in. It begins with a peculiar restraint—quiet, careful, and opaque—deliberately low-key in its visual grammar and narrative gestures. This quietude, far from a lack of confidence, is the slow tightening of a noose: each scene is calibrated to withhold, to mute, until the film slides almost imperceptibly into the realm of the domestic gothic. From there, it never settles. It morphs with unnerving grace, drifting between stylistic registers—now a somber chamber drama, now an eerie rural naturalism, now something near surreal—a psychological fugue rendered in flickers of sensuality and menace.

Claudio Guerín’s Bell from Hell unfolds like fog over a place once visited in a dream—recognizable in shape, but foreign in feeling, until dread fully settles in. It begins with a peculiar restraint—quiet, careful, and opaque—deliberately low-key in its visual grammar and narrative gestures. This quietude, far from a lack of confidence, is the slow tightening of a noose: each scene is calibrated to withhold, to mute, until the film slides almost imperceptibly into the realm of the domestic gothic. From there, it never settles. It morphs with unnerving grace, drifting between stylistic registers—now a somber chamber drama, now an eerie rural naturalism, now something near surreal—a psychological fugue rendered in flickers of sensuality and menace.

Renaud Verley plays John, a young man recently discharged from an asylum, returning to his childhood home under the pretense of reclaiming the inheritance left by his deceased mother. The estate, however, is now managed by his aunt and her three daughters—his cousins—who receive him with a strained civility that masks something deeply unsettled. What appears to be a story of madness—an unstable man disturbing the fragile balance of a respectable household—quickly fractures into something far more complex, a narrative of revenge and moral reversal, where outward order belies internal collapse.

Verley’s John is not merely a psycho; he is something worse: calculating, ironic, seductive. His insanity is at first assumed, even by the audience, but as the plot progresses, that assumption begins to dissolve into ambiguity. The signs of mental illness—his morbid jokes, erratic behavior, and manipulative games—are slowly revealed to be part of a far more coherent design. He exudes a sociopathic charm, insidious and deliberate, drawing his female cousins into incestuous games of seduction and psychological subjugation. One of them, we learn, was his lover in the past—a cruel entanglement that speaks volumes about the family’s history and their suffocating complicity.

The aunt, a crippled matriarch with a face as withered as her moral authority, at first looms like an obstacle, but she too is quickly neutralized—folded into John’s perverse theatre. Her authority, like the institutions she embodies, proves hollow in the face of his cunning. The power dynamics within the house collapse like old plaster. John stages his revenge not through overt violence (at least not at first), but through implication, through symbolic degradation, through the slow contamination of every relationship around him.

But his reach extends beyond the domestic. The villagers, too, fall under his sway—drawn to him by his irreverent charisma, or perhaps by the scent of scandal. He treats them with the same cold amusement, seducing and mocking them alike. In this sense, John is less a man than a symptom—a force revealing the hypocrisy and repression lying dormant in the family, the village, the broader society.

Despite the film’s naturalistic presentation—its rural settings, muted color palette, and grounded performances—there is something folkloric in its bones. The austerity of its aesthetic conceals a deep connection to the mythic and the ritualistic: the prodigal son’s return, the corrupt matriarch, the cursed inheritance. It feels less like a film concerned with plot than with unveiling a pattern of transgression repeating across generations.

Tragically, The Bell from Hell is haunted not only by its narrative content but by its own production. Claudio Guerín died on the final day of shooting, falling from the very bell tower that serves as the film’s central icon and metaphor. The bell, which in the film tolls for death and transformation, became the instrument of the director’s own demise. That eerie coincidence lends the film a spectral quality, as though it too were cursed—caught between fiction and fatality, performance and omen.

Yet the film is not merely a curiosity because of this coincidence. It is a work of profound subversion. Its true audacity lies not in its depictions of taboo—animal cruelty, sexual manipulation, even murder—but in how it frames these not as aberrations but as the inevitable byproducts of social and institutional decadence. The real horror lies not in John’s insanity, but in how justified it begins to feel. His vengeance is exacted upon systems that are already broken: a family built on repression and denial; a church represented by empty rituals and moral cowardice; a community more interested in appearances than justice.

In the end, the most empathetic character may well be the one most readily condemned. The madman, manipulator, sadist—he reveals himself as the only figure who sees things clearly, who acts without prejudgment, who exposes the deceitfulness of those around him. That inversion—where the sociopath appears more human than the institutions he dismantles—is where Bell from Hell finds its power. It tolls not only for the dead, but for the moral order itself.