Directed by Terence Fisher

Written by John Elder

Starring:

- Peter Cushing as Baron Frankenstein

- Susan Denberg as Christina

- Thorley Walters as Doctor Hertz

- Robert Morris as Hans

- Duncan Lamont as The Prisoner

- Peter Blythe as Anton

- Barry Warren as Karl

Rating: ![]()

A science-fiction drama that mutates, almost imperceptibly, into a spectral tale of vengeance—Frankenstein Created Woman is perhaps the strangest, most metaphysically ambitious entry in Hammer’s Frankenstein cycle. Is it even a Frankenstein film in any traditional sense? It’s hard to say. But what is certain is that this fourth installment, directed by the returning Terence Fisher, possesses an exquisite, disarming sensitivity and a curious spiritual gravitas that sets it apart—not just from its predecessors, but from nearly all horror films of its kind.

After Freddie Francis disrupted the series’ continuity with The Evil of Frankenstein, Fisher does not return to the linear progression he once established. Instead, he adopts Francis’s approach to reinvention—treating the Frankenstein myth not as sacrosanct canon but as pliable folklore, ready for transformation. The result is a film that, while bearing the Frankenstein name, is barely tethered to Shelley’s original premise. In that freedom, it finds its peculiar brilliance. If The Evil of Frankenstein was eccentric, Frankenstein Created Woman is downright esoteric—a fever dream of genres and tones, half gothic romance, half philosophical allegory. It is the least Frankensteinian of the Hammer Frankensteins, and also, paradoxically, one of the most profound.

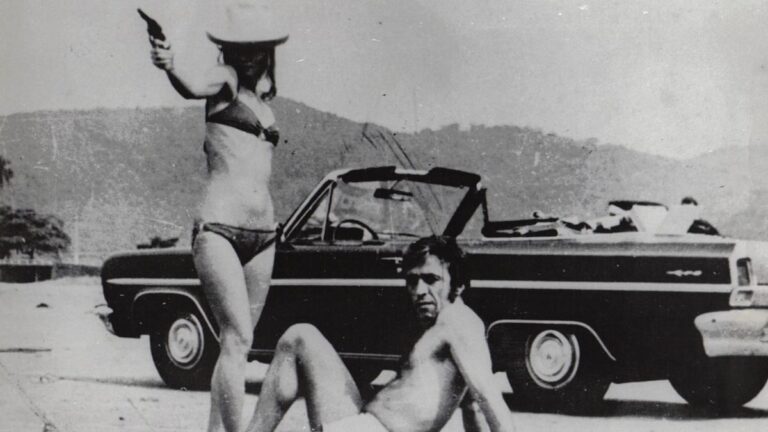

Peter Cushing’s Dr. Frankenstein, once the unholy heart of the series, now recedes into the background. His obsessive pursuits are no longer animated by scientific hubris, but by a quasi-mystical fixation on the nature of the soul. This shift allows the film’s emotional weight to fall squarely on Hans (Robert Morris), Frankenstein’s assistant and the son of a man guillotined before his eyes as a child. Hans emerges not as a stock sidekick, but as a fully realized tragic protagonist, a figure shaped by trauma and doomed by circumstance. The story orbits around his ill-fated love for Christina (Susan Denberg), a gentle, malformed young woman whose physical deformity has rendered her isolated and ashamed.

John Elder’s screenplay builds the narrative around the tragedy of Hans and Christina—not Frankenstein and his monstrous progeny—and this pivot transforms the film from gothic horror to poetic tragedy. Christina, mocked and tormented by a trio of aristocratic sadists, becomes the emotional fulcrum of the film. Her death, and eventual resurrection in a new, “perfected” body, gives way to a supernatural revenge plot that feels less like a genre obligation than the inevitable flowering of buried grief and rage. What begins as metaphysical speculation—abstract dialogues on the soul and consciousness—suddenly crystallizes into bloody purpose.

Denberg’s performance is striking: reserved, sorrowful, and deeply human, even as the film tilts into the uncanny. Morris, too, gives Hans a quiet dignity, grounding the film’s grander metaphysical ideas in lived emotion. Cushing, ever the professional, seems to understand that he is no longer the centerpiece and modulates his presence accordingly—clinical, reserved, almost spectral.

The title Frankenstein Created Woman suggests lurid melodrama, a promise of erotic horror that the film never quite fulfills—and yet, what it delivers is far richer: a strangely moving meditation on identity, grief, and transformation. Fisher, ever the visual classicist, cloaks the narrative in sumptuous color and painterly compositions, giving even the most outlandish scenes a sense of solemnity. This is Hammer at its most audacious—mixing pulp with metaphysics, vengeance with theology, sex appeal with soul-searching.

If The Bride of Frankenstein was Universal’s poetic apex, Frankenstein Created Woman may well be Hammer’s answer—a film that wears its strangeness proudly, and in doing so, becomes something unexpectedly sublime.