-Grindhouse Fest is the special section in Celluloid Dimension where you can discover all the goodies…and baddies from the golden age of exploitation cinema. Have fun!

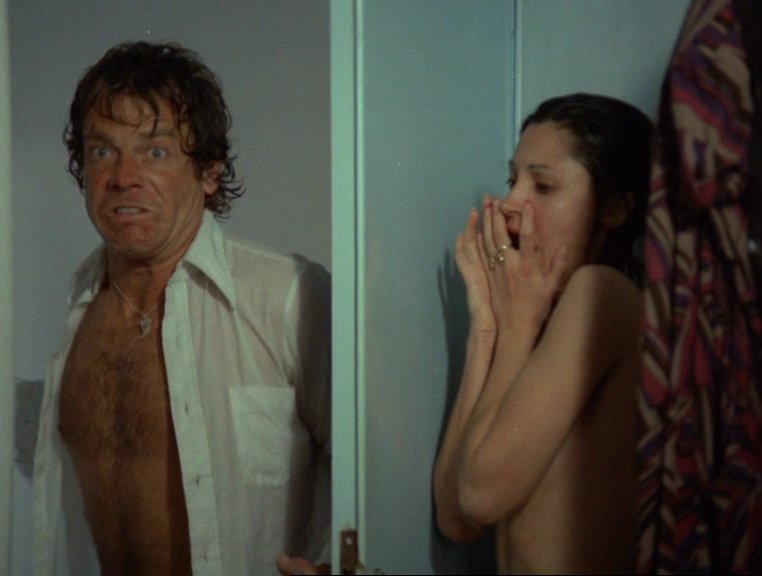

Directed by Nico Mastorakis

Written by Nico Mastorakis

Starring:

- Bob Behling as Christopher Lambert (credited as Bob Belling)

- Jane Lyle as Celia Lambert (credited as Jane Ryall)

- Jessica Dublin as Patricia Desmond

- Gerard Gonalons as Foster

- Jannice McConnell as Leslie (credited as Janice McConnel)

- Nikos Tsachiridis as Shepherd

Rating: ![]()

An exhausting, interminable smorgasbord of human perversion and… nothing else. One thing is sexual violence with a storyline, another thing is just plotless sexual violence; Nico Mastorakis’ unsympathetic exploitation Greek satire is just that, protracted torture porn with nothing to narrate. For starters, Island of Death’s tastelessness is tart even when viewed from the irony of its own humorous ontology – yes, the film goes out of its way to be harsher than its American counterparts, it is sadistic and excruciatingly sleazy, but its implementation of sadism is more that of a theater of the grotesque than of the downright horrifying – hence the berserk absurdist tone of the sexual violence always proceeds on a patently self-conscious plane, yet not genuinely comical in its cartoonish portrayal of the macabre, it is just a futile provocation incapable of yielding successful payoffs to determine whether it was worth watching an ultra-violent sequential tragicomedy of zoophilia, exhibitionism, sadism, incest, murder and every kind of sexual deviance you can imagine.

Shot on location on the stunning Greek island of Mykonos in the Mediterranean Sea, Nico Mastorakis’ disreputable Video Nasty is about a British couple, Christopher (Robert Behling) and Celia (Jane Lyle), who come to the tranquil, balmy seaside ambience of Mykonos to pursue their self-righteous depravity. Christopher assumes the role of a holier-than-thou inquisitor and Celia is his cohort in his heinous inquisitions. If the film is cleverly thought-provoking in any way, it is in its determination to portray Christopher’s noxious ideals as a hilarious oxymoron: he is an immoral moralist. His polemical social convictions and philosophical paradoxes may be intended to convey something meaningful about the toxic modus operandi of the art of exploitation, but its filth is more conspicuous than its candor, and its garish incompetence more flamboyant than its momentary professionalism, leaving on display nothing to redeem and nothing to highlight, only plenty to forget. By the time you reach the confines of its bizarre, karmic denouement – Is it the first exploitation movie to attempt to be a cautionary tale? – the only conclusion you come to is that the filmmakers must have been so busy stuffing lurid violent sequences into the film that they forgot to manufacture a plot around it.