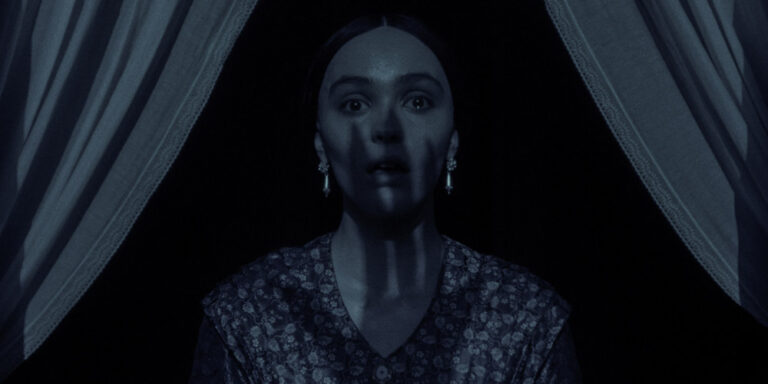

Directed by André Øvredal

Written by Bragi Schut Jr. and Zak Olkewicz

Starring:

- Corey Hawkins as Clemens

- Aisling Franciosi as Anna

- Liam Cunningham as Captain Eliot

- David Dastmalchian as Wojchek

Rating: ![]()

It was with a morbid delight—tinged with personal reverence—that I beheld André Øvredal’s cinematic rendering of The Captain’s Log, that most baleful and desolate chapter of Bram Stoker’s immortal Dracula. I had long considered this chapter the most terrifying and philosophically charged in the novel—a tale within a tale, a funereal voyage chronicled by a captain whose ink grows ever darker as his crew succumbs to an invisible malevolence. To see this chapter fleshed into images, into salt and blood and fog, was akin to revisiting a half-remembered dream: familiar and strange, sacred and profaned.

And so it begins: the merchant vessel Demeter, bound from Varna to Whitby, sailing into the unknown. Øvredal’s mise-en-scène—claustrophobic and cruel—transforms the ship into a tomb adrift. There is a poetry to its creaking timbers, a dirge in the way mist clings to the sails. The film captures, with admirable melancholy, the slow unravelling of order into dread. Yet where Stoker’s prose was suggestive, elliptical, Øvredal’s camera, at times, bares too much. Dracula himself—rendered here not as the seductive count but a gnarled, almost Nosferatu-like beast—is shown with the kind of explicitness that threatens to banish mystery. And still, there is power in his form, in the way evil manifests as a thing ancient and indifferent.

The film reimagines the crew’s tragedy as not only a confrontation with death but with meaninglessness. Clemens, the ship’s learned physician, seeks solace in astronomy and logic, only to find both instruments impotent. His struggle becomes emblematic of a larger battle—one not merely of man against monster, but of enlightenment against the abyss. The conflict between reason and superstition, science and faith, plays out not in grand discourses but in glances, hesitations, quiet mutinies of the soul.

In its best moments, the film reminds us that terror lies not in what is seen but in what is sensed: the fear of an unnameable presence, the disintegration of camaraderie, the inescapable pull of doom. Øvredal dares to give voice and form to these ineffable tensions, and while his methods are sometimes blunt, the emotional truth remains intact.

It’s part prestige adaptation, part creature feature, and part theological parable—all wrapped around a single chapter from Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Thus, this voyage—like the Demeter itself—sails on toward its ghastly destination, not as a triumph of cinema perhaps, but as a haunted tribute to one of horror literature’s most spectral passages. It is a requiem for a lost crew, and perhaps, for all of us who peer too long into the darkness and find that the darkness peers back.