Directed by Victor Erice

Written by Victor Erice and Miguel Gaztambide

Starring:

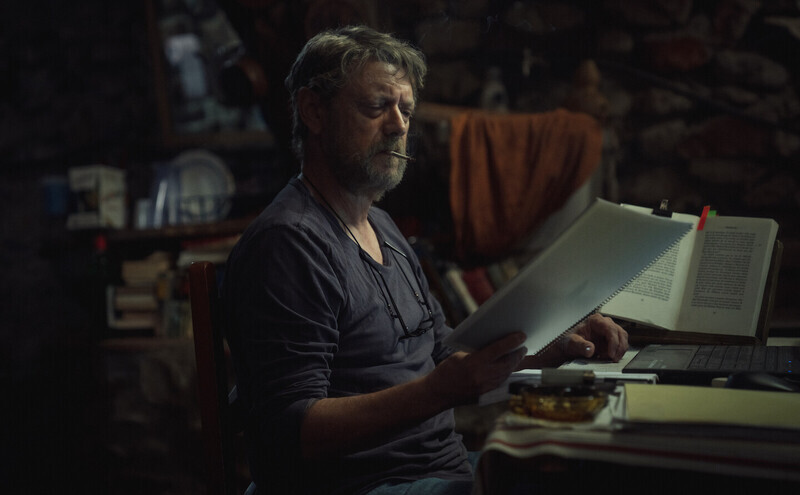

- Manolo Solo as Miguel Garay

- José Coronado as Julio Arenas / Gardel

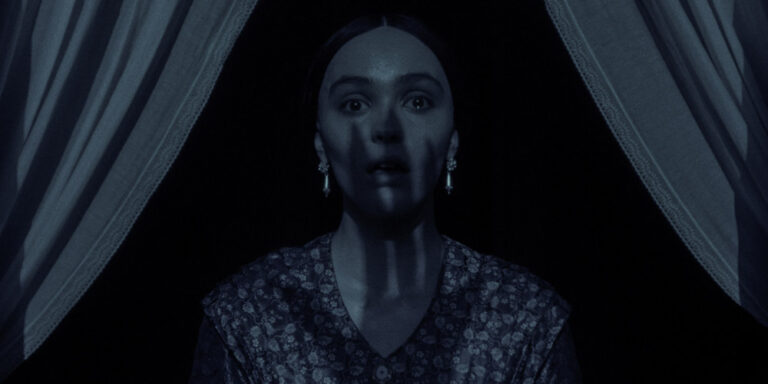

- Ana Torrent as Ana Arenas

- María León as Belén Granados

- Petra Martínez as Sister Consuelo

- Soledad Villamil as Lola San Román

- Antonio Dechent as Tico Mayoral

Rating: ![]()

Memory is an intricate and intangible archive of lived experience, shaped by emotion and filtered through time. In many ways, its ontology echoes that of celluloid—the fragile, flammable material on which cinema was historically etched. Just as memory is vulnerable to distortion or decay, so too is the film strip: delicate, susceptible to erosion, yet capable of preserving moments with startling clarity. The human mind, much like a reel of exposed film, carries impressions—both vivid and vague—of the past. It is this deeply poetic analogy between memory and cinema that Victor Erice explores with profound lucidity in his monumental return to feature filmmaking, Cerrar los ojos. No written reflection can truly do justice to the emotional and intellectual density of this film, but it compels one to try.

After a three-decade hiatus from the full-length format, the master of Spanish cinema re-emerges with a meditative and majestic work that feels less like a comeback and more like a benediction. With The Spirit of the Beehive (1973), Erice introduced himself as a visionary—capable of rendering Spanish history and childhood trauma with an almost supernatural stillness. His follow-up, El Sur (1983), confirmed his stature: a poetic and intimate portrait of memory and distance. Then came El sol del membrillo (1992), a documentary that blurred the line between painting and cinema. After such a prolonged silence, Cerrar los ojos arrives like a whispered revelation, and it is, remarkably, one of Erice’s most ambitious works.

What sets this film apart from his earlier oeuvre is its intellectual directness. If his previous films communicated through silence and subtlety, this one speaks—at length and with urgency. Written with Michel Gaztambide, the screenplay is Erice’s most verbose, a deliberate shift from the visual minimalism of his past. And yet, this isn’t verbosity for its own sake. The dialogues carry philosophical weight, unfolding like soliloquies shaped by time and loss. The visuals remain restrained and contemplative—patient, even religiously so—but the film’s engine is language. Erice has crafted a cinematic essay on the power of memory, the ethics of art, and the mystery of human disappearance.

The plot opens with a metafictional conceit: a film within a film. The actor Julio Arenas (José Coronado) vanishes mysteriously during the shooting of a 1990s production. The opening sequence we see is from that unfinished movie—fragmented, incomplete. Two decades later, a television program reopens the cold case, reaching out to Miguel Garay (a soulful Manolo Solo), the director and close friend of Julio. Miguel agrees to be interviewed, seemingly for the money, but as the questions unearth old wounds, he finds himself drawn back into a labyrinth of memory, guilt, and unresolved grief.

What follows is not merely a mystery about a missing actor, but an ontological inquiry into loss—personal, artistic, and existential. The film’s languid pace and understated visual grammar echo the stillness of a life arrested by trauma. As Miguel revisits the people once connected to Julio—his daughter Ana (played poignantly by Ana Torrent), former collaborators, acquaintances—the film gathers emotional momentum. These aren’t just interviews; they become confessions, reflections, and fragments of a collective memory that refuses to settle into certainty. The further Miguel digs, the more the search becomes less about Julio and more about himself.

In this sense, Cerrar los ojos becomes an immersive act of self-interrogation. Miguel’s crisis is universal: Who are we without our memories? What remains of us when those memories are incomplete, or worse, fictionalized? The film masterfully channels the philosophical undercurrent of Proust, the emotional restraint of Ozu, and the spiritual inquiry of Tarkovsky—yet it remains unmistakably Erice. There’s a humility to his direction, a refusal to sensationalize, even in the most emotionally fraught moments.

At the core of this elegy is a meditation on the symbiotic relationship between memory and cinema. Erice does not merely present film as a metaphor for memory—he shows cinema as memory, as its mechanical and emotional double. In a breathtaking final sequence, Miguel and other characters gather in a modest theater to watch the rediscovered footage from the unfinished film. The analog projection flickers to life, enveloping them in darkness, and what they witness is both hauntingly familiar and heartbreakingly transformative. These images, seemingly lost to time, suddenly become vessels of truth, redemption, and identity.

The power of this ending lies in its ambiguity. Erice does not resolve the mystery. He offers no catharsis, no tidy answers. Instead, we are left with a sublime uncertainty—an emotional paradox that mirrors the instability of memory itself. Has Julio truly returned? Or have the characters merely found closure in illusion? The film does not say. It merely invites us to watch, to listen, and to remember.

Cerrar los ojos may be Erice’s most philosophical film, and also his most generous. By confronting his own questions—about art, memory, and meaning—he gives us the space to ask our own. It is a deeply humanistic work, suffused with empathy and melancholy. And though it departs from the visual austerity of his earlier films by embracing language, it does so without sacrificing poetic resonance.

All things considered, the film lives up to its title. Perhaps we must close our eyes—not to escape reality, but to better perceive the images that truly matter: those imprinted on the celluloid of our minds. In the interplay between cinema and remembrance, Victor Erice has crafted not just a film, but an act of quiet transcendence. It may be the finest work of his career since The Spirit of the Beehive—and perhaps even its spiritual equal.