Directed by Makoto Shinkai

Written by Makoto Shinkai

Starring:

- Nanoka Hara as Suzume Iwato

- Hokuto Matsumura as Souta Munakata

- Eri Fukatsu as Tamaki Iwato

- Shôta Sometani as Minoru Okabe

- Sairi Itô as Rumi Ninomiya

- Kotone Hanase as Chika Amabe

- Kana Hanazawa as Tsubame Iwato

- Ryûnosuke Kamiki as Tomoya Serizawa

- Ann Yamane as Daijin

Rating: ![]()

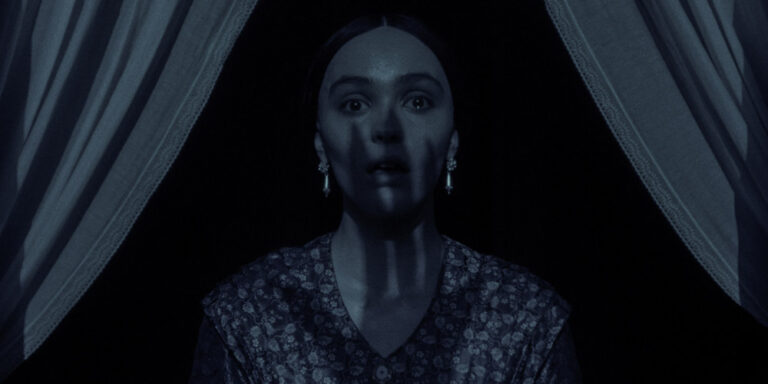

Makoto Shinkai’s Suzume is spectacularly absurd yet undeniably familiar. Lacking the philosophical romanticism and cosmic intricacies of Your Name and the metaphorical beauty of Weathering with You, it nevertheless follows the same emotional rhythm, continuing the fanciful animated poetry that Shinkai has meticulously crafted—brick by brick, frame by frame—throughout his erratic yet now prestigious career.

Having achieved back-to-back box office triumphs with Your Name (2016) and Weathering with You (2019), Shinkai once again proves himself a master at transforming prosaic coming-of-age narratives into poetic romantic anime fantasies. Suzume, in all its unabashed sincerity, underscores how his signature blend of quirky storytelling and convoluted emotionalism has evolved into an indispensable fixture in his artistic explorations. Because of this, Shinkai’s latest feature is hardly novel. Detractors might dismiss Suzume as yet another dose of saccharine, juvenile melodrama, recycled from his previous works—but rather than a flaw, I see this repetition as Shinkai’s greatest strength. If rehashing a functional formula ad nauseam is a blemish in his filmography, then I must confess my admiration for that masterful imperfection.

At its core, Shinkai’s equation is simple yet strikingly effective:

- A classically romantic narrative, seemingly pulled from the reveries of a teenage girl—both grounded and fantastical, sober yet frenzied.

- A thematic foundation laden with intellectual impetuosity—deliberately intricate, teetering on the edge of chaos.

- An audiovisual exuberance that channels folklore, mythology, and the rich fantasy principles of literary tradition.

These elements imbue his films with grandeur and resonance, and though Suzume may not be the pinnacle of his oeuvre, it is arguably the most refined expression of his programmatic formula. Not necessarily superior to Your Name or Weathering with You, it lacks the same emotional heft to rank alongside them, yet in its composition and execution, it remains exquisitely ceremonious—brimming with moments that astound.

Suzume Iwato (Nanoka Hara) is a curious and sweet-natured 17-year-old living with her protective aunt, who has raised her since she lost her mother as a child. Haunted by fragmented memories of that loss, Suzume’s fate shifts when she encounters a mysterious young man named Souta (Hokuto Matsumura), a “closer” tasked with shutting doors that, if left open, can unleash catastrophic disasters. True to Shinkai’s sentimental blueprint, Suzume falls for Souta at first sight and follows him with reckless devotion. Their journey becomes a fantastical odyssey of self-discovery—complicated when Souta, by way of a bizarre curse, is transformed into a sentient wooden chair.

Though easy to dismiss as childish, Shinkai’s whimsical conceits, when viewed as figurative devices, reveal a profound emotional resonance. The absurdity of a talking chair becomes not merely an imaginative flourish but a deeply meaningful emblem of Suzume’s struggle with grief, reinforcing Shinkai’s signature motif: human connections and the way relationships shape our destinies. Suzume’s love for Souta leads her to confront her trauma, intertwining the metaphysics of love with the tangible labyrinth of existence.

Shinkai’s radiant style capitalizes on the limitless potential of animation, crafting a fantasy landscape steeped in fable yet unmistakably modern. Suzume, though set in 2023, is tethered to Japan’s past, mirroring the spiritual and seismic upheavals woven into the nation’s history. Japanese audiences likely perceive in Suzume’s folkloric echoes a poignant metaphor for the natural disasters their country has endured, making the film not only emotionally evocative but historiographically significant.

Beyond its lyrical grandeur and dazzling spectacle, Suzume thrives in its moments of quiet romantic introspection. Shinkai, ever the operatic conductor, orchestrates stunning sequences in which music, animation, and kinetic storytelling synchronize to create breathtaking cinematic poetry. His work exemplifies the fearless exploration of anime—a medium unrestricted by the constraints that often bind Western animation.

While Suzume treads familiar ground, it remains a testament to Shinkai’s mastery. His understanding of teenage love, existential longing, and the profound interplay between memory and identity is so acute that even his most formulaic repetitions feel fresh. The film’s playful intricacies—particularly the movements of its mischievous cat and animated chair—carry a joyous, infectious energy. Ultimately, it is through this humble chair, handcrafted by Suzume’s mother, that Shinkai distills the film’s essence. Like an anime “Rosebud,” it encapsulates Suzume’s journey, proving that whether material or ethereal, memories are the threads that shape who we are.