Directed by Demian Rugna

Written by Demian Rugna

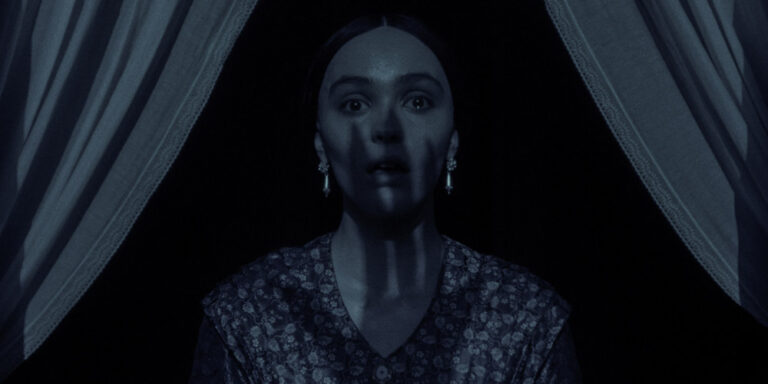

Starring:

- Ezequiel Rodríguez as Pedro

- Demián Salomón as Jimi

- Silvina Sabater as Mirtha

- Luis Ziembrowski as Ruiz

- Marcelo Michinaux as Santino

- Emilio Vodanovich as Jair

- Virginia Garófalo as Sabrina

Rating: ![]()

Friedrich Nietzsche’s ominous declaration, “God is dead,”—denoting the absolute disintegration of moral truths and the collapse of religious authority—has seldom felt as vicious and eerily tangible as it does in When Evil Lurks, Demian Rugna’s merciless vision of horror. This Argentine nightmare does not merely disturb; it festers, dissecting modern civilization at its most corrosive—where the unchecked greed of advanced capitalism devours the first world, and the illusion of prosperity crumbles within the corruption of the third.

What outwardly masquerades as a visceral film of demonic possession conceals a conceptual monstrosity beneath its decaying façade—an acrimonious behemoth, an unrelenting machine of dread that commandeers the genre’s conventions only to distort them with venomous precision. The film transmutes familiar demonological absurdities into something far more harrowing: a deeply unsettling, apocalyptic meditation on a modernity consumed by its own arrogance, ignorance, and festering fears.

Rugna imbues When Evil Lurks with a contemplative coldness—a fury that divorces it from conventional supernatural horror, elevating it to a cinematic philosophy of nihilistic terror. Its fatalism is uncompromising, shredding any semblance of hopeful luminosity, ensuring that its horror is not merely experienced but absorbed. While it acknowledges the lineage of genre greats—films it humbly eulogizes—its method is wholly its own, wielding noxious materials with an unparalleled effectiveness that does not possess the audience with demons but infects them with a penetrating social rigor, stripping away humanitarian sentiment in favor of unrelenting pessimism. Given the contemporary anxieties that pervade our age, When Evil Lurks is more than essential—it is inevitable. This is the horror film that 2023 demanded, and here it stands, merciless and undeniable.

While When Evil Lurks certainly embraces familiar tropes of possession horror, its true foundation lies in the superstitious folklore that dictates its narrative logic. Demian Rugna is, at his core, a realist rather than a romanticist, and this anti-lyrical stance allows him to conceive horror not as mere spectacle, but as a terrifying speculation—an unsettling what if scenario that asks: What if the religious myths that have long burdened us with guilt and fear were not fabrications, but undeniable realities?

Rugna’s film offers a deeply disturbing answer to this question, rendering an unnervingly plausible vision of a world where supernatural terror is not just mythological but tangible. The narrative unfolds like a formidable biblical yarn, reminiscent of monotheistic literature that warns of the catastrophic consequences of underestimating or defying evil. The depiction of possession here transcends mere genre convention—it is an all-consuming, systemic affliction that does not manifest with arbitrary chaos but follows an ancient, inescapable structure. If the existence of metaphysical, demonic evil were real, one could argue that the infernal hecatomb witnessed in When Evil Lurks would be its perfect manifestation. Even from its opening moments, the film plunges the viewer into an eerie liminality between material rationality and supernatural irrationality—forcing them to question which world we truly inhabit. The setting is crucial: a rural, desolate landscape, far removed from urban modernity. Pedro (Ezequiel Rodríguez) and his brother Jimi (Demián Salomón) live in these remote, demoralized areas, where isolation heightens vulnerability. One night, they hear gunshots deep within the woods, and their investigation leads them to a gruesome discovery—a mutilated corpse, severed in two. This horrifying omen soon directs them to a decaying home nearby, inhabited by a woman and her two children. One of them—a grotesquely ill, morbidly obese man—teeters at the edge of death, his bloated body corrupted by an unseen force. He is not merely sick—he is Rotten, a term used to describe those unfortunate souls in whom demons gestate before being born into the world.

The folklore governing Rotten individuals is strict, functioning under a set of ritualistic laws that impose rigid limitations on how their presence can be handled. The most chilling of these rules dictates that they cannot be killed conventionally—taking their lives through violence ensures that the curse will proliferate rather than end. Yet Pedro and Jimi, overwhelmed by paranoia and neurosis, fail to adhere to these warnings, setting off an irreversible catastrophe. What makes Rugna’s approach singular is his insistence on treating possession with a speculative logic that feels disturbingly coherent. The film does not rely on arbitrary supernatural threats—it builds a structured, folkloric horror that obeys an internal rationale, making its terror feel not just fictional but feasible. As the narrative unravels, it does not entertain survival—it entertains inevitability.

In the wake of the post-2020 era, where fear of contagion reshaped collective psychology, When Evil Lurks channels this lingering trauma into a vision of possession as a multiplying, uncontrollable force. While the film avoids explicitly framing its horror as a pandemic allegory, it undeniably taps into post-traumatic anxieties—transforming societal dread into a nihilistic manifesto that operates with brutal precision. This is not merely a story of demonic affliction but a parable of unchecked contamination, one that thrives not simply on supernatural terror but on the irrevocable mistakes made by those who believe they can outmaneuver the abyss.

Predictably, the film’s descent into chaos is triggered by a single, ill-conceived decision: Pedro, Jimi, and another landowner attempt to remove the Rotten from their land, believing that displacement will sever their ties to the evil festering within him. But superstition, much like contagion, does not abide by territorial logic. The horror does not dissipate with relocation—it escalates. Their reckless impulses do not expel the threat; they ensure its proliferation.

In the midst of this descent, Rugna layers his film with subtle but profound curiosities. Foremost among them is the class disparity embedded in the story—the Rotten, the unfortunate vessel through which the demonic affliction manifests, is a man of destitute socio-economic standing. He is poor, neglected, relegated to the margins of society. This is not incidental. Whether intentional or subconscious, Rugna’s choice speaks volumes: in a world shaped by systemic inequality, evil is not merely a supernatural force—it is the manifestation of prejudice itself. The infection, much like social stratification, spreads in ways dictated by existing hierarchies, reinforcing the tension between the privileged and the damned. Equally pervasive is the film’s meditation on faith—or rather, its absence. While none of the characters openly renounce belief, there is a pervasive sense of abandonment. God has forsaken them, or perhaps they have forsaken Him. The secularism that pervades their decisions is not explicit but quietly corrosive. Fear reigns supreme, and superstition replaces theological certainty. Yet the horrors they encounter force them into an unwinnable crisis of belief—one that obliterates them before they can even articulate their doubts.

For the unbelievers who mistake this philosophical exploration as sermonizing, it is worth noting that When Evil Lurks does not moralize—it externalizes. It does not preach about faith or its necessity; it illustrates the perilous consequences of amorality within a world built upon rigid moral distinctions. Pedro, driven by desperation, succumbs to an ethical blindness that fractures his ability to judge his own actions. He no longer trusts himself, nor does he trust the structures that once governed his understanding of good and evil. In this way, the film’s horror is not simply supernatural—it is psychological. It is the terror of losing control, of watching civilization dissolve into incoherence.

The core of When Evil Lurks is intensely compelling because it exploits contemporary vulnerabilities to forge a terror that is both false and true—a horror that rejects objective explanations, drawing instead from the murky depths of speculative dread. Demian Rugna’s urgency in dramatizing possession as more than a mere supernatural occurrence—as a symbolic premonition of our fragile, decaying future—is palpable.

In contrast to the juvenile rhetoric that dominates much of modern horror—films that rely on trauma-based evocations for immediate shock value—Rugna refuses to tread that facile, minimalist path. Instead, When Evil Lurks embraces extremity with unflinching maturity, carving out a place for itself in the genre’s more uncompromising lineage. Its moments of startling malice are not gratuitous—they are among the fiercest set pieces in recent horror, executed with a rawness and confidence that distinguish the film from the saturated landscape of possession stories. Yet its greatness does not stem merely from cinematic bravado. What makes When Evil Lurks remarkable is its ability to fuse nihilistic entertainment with an articulation of miserabilism—a bleak, resonant commentary on contemporary anxieties that never dilutes its severity for accessibility. The experience is throbbing, relentless, an imminent danger that refuses to loosen its grip. If, at any point, it does release you, it is not out of mercy—it is only because you failed to look deeply enough into the abyss it presents.

To end with the same Nietzschean meditation with which this began: “If you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.” Few films embody this idea as eloquently and as frighteningly as When Evil Lurks.