Killers Without a Cause

The Philosophy of Evil in Some Visitors: A Home Invasion Film Beyond Convention

In contemporary Western society, where the pursuit of immediate gratification dominates cultural narratives and hedonistic consumerism dictates entertainment, films that challenge this superficial optimism are exceedingly rare. The prevailing ethos, particularly in American media, propagates a vision of fulfillment and prosperity as universal aspirations—often sidelining darker truths about human nature. This is precisely why Some Visitors, a deceptively simple yet profoundly unsettling short film, resonates with such raw power. It refutes the complacency of conventional humanism, rejecting the naïve conviction that morality is intrinsic to the human condition.

At first glance, Some Visitors seems to operate within the well-worn framework of a home invasion thriller, a subgenre explored ad nauseam in both independent and mainstream cinema. Yet Paul Hibbard’s film transcends its format, using the familiar narrative structure as a vehicle for deeper sociopolitical and philosophical interrogation. It does not merely depict terror; it examines the very essence of violence, misanthropy, and moral ambiguity. The film’s fundamental question—whether evil is exogenous, a force imposed upon individuals, or endogenous, an inherent aspect of humanity—remains deliberately unanswered. Instead, it forces viewers into a disquieting space where certainty dissolves, leaving only the realization that violence does not always require rationale.

To contextualize this idea, Some Visitors inadvertently echoes the paradox of Rebel Without a Cause (1955). Nicholas Ray’s classic film presents a youth culture characterized by defiance, its title ironically suggesting a lack of motivation when, in reality, the rebellion portrayed has clear social and psychological catalysts. Unlike Rebel Without a Cause, however, Some Visitors strips its antagonists of even the pretense of causality. Here, there is no justification—not for the rebels, but for the killers. Hibbard constructs a world where the perpetrators of violence exist without deeper motivations, functioning not as products of trauma or systematic failures but as manifestations of inherent malice.

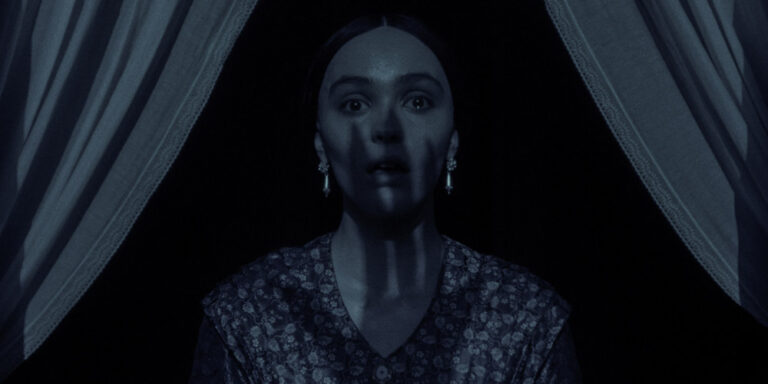

The film immediately establishes its unnerving tone through a statistical prelude, referencing the rising threat of home invasions in American households. This introductory device serves as more than mere exposition—it signals the film’s engagement with societal paranoia, positioning vulnerability as an inescapable condition. Jennifer (Jackie Kelly), the protagonist, embodies this existential tension. She is acutely aware of the dangers lurking beyond the threshold of her home, conditioned by media-fueled anxieties surrounding random acts of violence. When Jeff (Clayton Bury), a seemingly distressed stranger, arrives at her doorstep claiming to need help after a car accident, she hesitates. Her instincts warn her of danger, yet she ultimately yields to an ingrained moral impulse—the parable of the Good Samaritan triumphing over rational apprehension.

From this moment, Some Visitors meticulously orchestrates its discomfort. Jennifer and Jeff’s exchange unfolds with slow-burning hostility, their conversation tinged with veiled menace despite its outward civility. Hibbard’s direction favors verbosity over immediate action, allowing dread to fester within the dialogue rather than resorting to conventional horror tropes. The verbal sparring between the two characters is restrained yet charged, exposing a psychological battleground wherein trust and deceit are indistinguishable. Jennifer’s fragility emerges through her reluctant engagement, while Jeff’s inscrutability generates an escalating unease.

Crucially, the film’s misanthropic thesis begins to take shape when Jeff derisively acknowledges Jennifer’s personal tragedy—the death of her child. His flippant tone renders her pain into something grotesquely performative, mocking the vulnerability that she has no choice but to reveal. This moment underscores the film’s rejection of sentimentalized victimhood. Jennifer, though initially positioned as sympathetic, soon becomes an avatar of Some Visitors’ philosophical cynicism. She is not merely a victim of circumstance—she is a victim of trust itself.

As the invasion escalates, the narrative abandons any semblance of order. Additional intruders—a woman and another masked man—join Jeff in violating Jennifer’s sanctuary, dismantling the thin barrier separating civility from savagery. The film does not merely depict brutality; it systematically erodes the viewer’s moral compass, forcing an uncomfortable reconciliation with the idea that goodness is neither inherent nor reliable.

This thematic upheaval is perhaps best encapsulated in the film’s climactic betrayal. The audience, conditioned to sympathize with Jennifer, is abruptly confronted with an unsettling truth: there are no trustworthy characters in Some Visitors. Its ultimate revelation is not simply that evil exists, but that it exists without prejudice or distinction. The film challenges its viewers to reconsider the very concept of moral redemption, suggesting that even the victim is ensnared within the cycle of violence.

Hibbard’s refusal to offer a clear resolution reinforces Some Visitors’ philosophical audacity. Unlike mainstream thrillers that hinge on either moral restoration or catharsis, this film abstains from absolution altogether. It presents humanity not as redeemable, but as fundamentally compromised—a notion that conflicts with the pervasive optimism of Western ideology. The film’s bleak finale cements this perspective, dismantling institutionalized narratives that insist society can correct its deepest flaws through systemic reform or moral education.

This uncompromising vision situates Some Visitors as an incendiary critique of contemporary sociopolitical discourse. In modern America, there is an obsessive drive to seek explanations for every act of brutality—to rationalize atrocity through environmental, economic, or psychological causality. The prevailing assumption is that dysfunction can be traced to structural inadequacies rather than existential inevitabilities. Hibbard’s film directly refutes this notion, arguing that to insist upon explanations is, in some cases, to diminish the weight of evil itself. It is not that Some Visitors necessarily advocates for nihilism, but rather that it exposes the limits of moral rationalization.

Its conclusion—both narratively and philosophically—stands as a direct rejection of institutional reassurances. Governments, media, and educational bodies perpetuate the comforting idea that crime stems from solvable social conditions rather than from inherent moral deficiencies. Some Visitors dares to suggest otherwise. It does not seek to diagnose the pathology of violence; it simply shows that it exists, and that sometimes, no amount of optimism can negate its presence.

In barely half an hour, Some Visitors achieves something few contemporary horror films dare to attempt. It unearths existential anxieties that linger beneath the surface of modern discourse, stripping away comforting delusions about human nature. Its performances—Clayton Bury and Jackie Kelly delivering a harrowing study in dramatic duplicity—elevate the material beyond genre conventions. Its technical execution, precise and unrelenting, reinforces its thematic brutality.

Ultimately, Hibbard’s film is more than just a revisionism of the home invasion subgenre—it is an indictment of blind faith in human goodness. It is audacious in its thematic ambitions, fearless in its execution, and unrelenting in its perspective. To call it merely “mean-spirited” would be an understatement—it is a film designed to disturb, provoke, and dismantle illusions that contemporary Western culture often takes for granted. Some Visitors is not interested in providing comfort; instead, it forces its audience to confront the unsettling possibility that trust, even in its most basic form, is nothing more than an illusion.