![]()

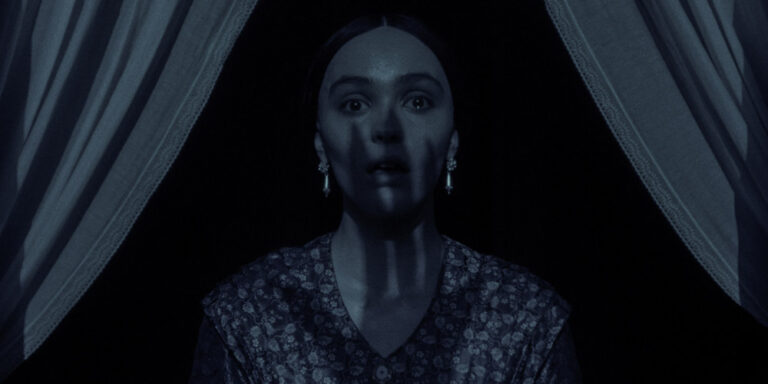

Master Gardener (2022) Directed by Paul Schrader

Paul Schrader’s repetitive moral theology is not subtle, the conspicuousness of his tempestuous metaphysics seldom goes anywhere worthy of being called transcendental. He is not a subtle filmmaker; his style is implanted in thematic indiscretion. I suspect that his orthodox Calvinist upbringing has much to do with this urge to be obvious in categorically moral matters. Growing up under the reformist scrutiny of Calvinism must have shaped his way of looking at things, particularly the materiality of the world and the spirituality of it, and likewise that of cinema itself. Living under sanctimonious prejudices represses human identity with such forcefulness and stringency that circumspection practically possesses you for bad and for good; thus, calling into question everything you wish and want to express. Evidently, Paul Schrader’s films manifest the liberation of a filmmaker in conflict with his asphyxiating and restrained past; a past that has given him the necessary explicitness to justly emancipate himself from his demons. Replete with analogies, Paul Schrader’s brooding and poetic Master Gardener boasts a renewed flowering of his rhetorical flair, and while the thematic iteration remains the same as in his other films, the dramatic cadence here is formidable and entrancing. The exercise is minimalist but its depth maximalist, and though I’ve always believed Schrader to be a better writer than director, I sense that this is the first film of his that slightly makes me want to change my mind.

There is an omnipotent artistry in the visual architecture of this film that enlivens with mercy and moral complexity the mortifications of its deeply flawed characters, leaving on view an achingly beautiful and terrifying story that is simply impossible to evade. The metaphors rapidly become trite and hokey, yet the plot is perennially clever in its use of them for its perspicacious dramatic development. If you’re familiar with Paul Schrader’s films, you can tell by now that you know the plot of this film without ever having seen it, the journey is predictable, you can even tell when and how turbulence will arise. However, Schrader’s age – now in his late seventies – suggests that he is more mature to elaborate philosophical conundrums. Consequently, his predictable narrative style moves ever closer to a conclusion that aims to sum up his influential career. Joel Edgerton – in his most convincing and commanding acting form – plays the lonely and mystifying new protagonist in Paul Schrader’s mythology, the stern and dutiful Narvel Roth, an artful gardener working at the sophisticated Gracewoods garden estate, owned by the manipulative millionaire Norma Haverhill, played sublimely by Sigourney Weaver. Narvel is a kind man, very courteous and correct, but those ethical qualities are only part of his present; he conceals his sordid past, with his horticulturist’s clothes and gestural secrecy. He is passionate about gardening; he treats each plant and flower as a poet treats the metrics of his verses. Horticulture is a means of expression for him, in which he channels his demons of the past and sublimates his sins. The morally convoluted vicissitudes of the plot emerge when the eloquent Mrs. Haverhill asks Narvel to do her a favor, to teach all his gardening wisdom to her orphaned grandniece Maya, played by Quintessa Swindell, and to take care of her as she is a wayward girl with a drug problem.

The coordination of the camera movements – which testify to the tragic poetry of the characters – is cunningly composed to distance us from the poignancy that certain passages may arouse. To some, the classical estrangement effect employed to exhaustion in Schrader’s films may feel pretentious, but here its implementation is instinctive. Just as Narvel distances himself from his bleak past and eschews introspection or self-criticism, Alexander Dynan’s sobering cinematography in conjunction with Schrader’s radical alienating style seeks to interrupt the emotional passages to intellectualize the moral controversy Narvel and we as an audience go through. The question that almost all of Paul Schrader’s work leaves you with is this: Can a person achieve redemption in spite of their crimes? Personally, I don’t think the director’s soteriology is an uncompromising quest to redeem questionable characters, much less force his audience to condone, but rather something tells me that he pursues ambiguity as a mechanism of abstraction. Narvel is as irredeemable as he is redeemable, once you learn what was his hostile past that haunts his present the ugliness of his crimes removes any trace of possible redemption, but when his present actions, specifically those in which he seeks the salvation of a lost young girl like Maya, involve a soulful humanity that evokes the compassion one feels for someone who has committed mistakes and aims to remedy them, redemption seems attainable. Schrader’s determination to instill an aura of ethical ambivalence in the particulars of his style is admittedly questionable, it doesn’t necessarily work as a film to be debated in its after viewing. In theory, Master Gardener is more intriguing in the realm of discussion regardless of its function as a film. I don’t know if that’s a positive or a bad thing, but the visceral effects here are unequivocal, even given the intellectual intransigence of such academic writing as Schrader’s, the film is potently emotional, to the extent of challenging your own morality.