Directed by Pablo Larrain

Written by Guillermo Calderon and Pablo Larrain

Starring:

- Jaime Vadell as El Conde (Augusto Pinochet)

- Gloria Münchmeyer as Lucía

- Alfredo Castro as Fyodor

- Paula Luchsinger as Carmencita

- Stella Gonet as Margaret

Rating: ![]()

Vampires and tyrants are theoretically interchangeable, regardless of the mythology to which they belong. Both have appetite for power and despotic ambitions that can only be satiated by subjugating the weak and helpless with their persuasive enchantments. The difference is that the former uses a metaphysical seduction that is too magnetic and therefore impossible to be resisted, and the latter uses the same metaphysics but is eloquently verbal, cajoling his listeners with the spurious narrative of political populism. Simply put -and in the most metaphorical expression possible- both feed on the ignorance of the people; they are indefatigable bloodsuckers.

Pablo Larrain’s delirious political satire El Conde is too ambivalent to know exactly what it intends to do with its farcical revisionism of one of the most notorious figures -adored by others- of Chilean history. The monstrously sardonic storytelling deals with issues that are inherently very sensitive to society at large, so I am not surprised by the inharmonious reactions this film has provoked in the audience. The irreverent and fantastical portrayal of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in the form of a vampire can err on the side of frivolity. Consequently, it is very difficult to determine whether Larrain’s agenda was a simple satirization of Pinochet or just a heartless spoof. Turning an odious personage in Chilean history into a decrepit vampire and transforming his crimes into a kind of gothic opera is not the most appropriate format to criticize Pinochet’s heritage in contemporary times. However, Pablo Larrain has made it clear that he is a staunch opponent of anti-democratic individuals – this is not the first time he has created a film manifesto against Pinochet.

El Conde in my humble assessment is more a satire of the intoxicating love affair that human beings have with being powerful. Lust, immortality and socio-economic power have been the ambitions -some of these are allegorical of course- of all the most nefarious authoritarian rulers in contemporary history. All of them seek the chimerical concepts of immortality through the cult of their personalities; in grand pictures, in hymns and artistic exaltations, in panegyrics and mausoleums, all these egocentric and pseudo-omnipotent characters since the French Revolution have been nothing more than incorrigible misanthropes and narcissists obsessed with their fantasies of greatness and domination.

The simple juxtaposition of vampire lore with the totalitarian desires of a tyrant provides a hysterical quality to the madcap yarn that Larrain directs and co-writes. In my view, El Conde is not acerbic enough to be a laudable indictment of Pinochet, yet it is an uncanny, brooding, and outrageously compulsive vituperation directed against the idealization of the dictator. From the beginning of the film, a sublimely cynical narration chronicles the origin of El Conde (caustically played by Jaime Vadell) -who would later become the most powerful man in Chile by carrying out a military coup against the socialist government of Salvador Allende in 1973- from his bloodthirsty youth years in France in the 18th century to becoming a ruthless counterrevolutionary infiltrator in all the major revolutions in history. After a long blood-sucking adventure he decides to fake his death to start a new life in a South American country where he would adopt the name Augusto Pinochet. The rest is history.

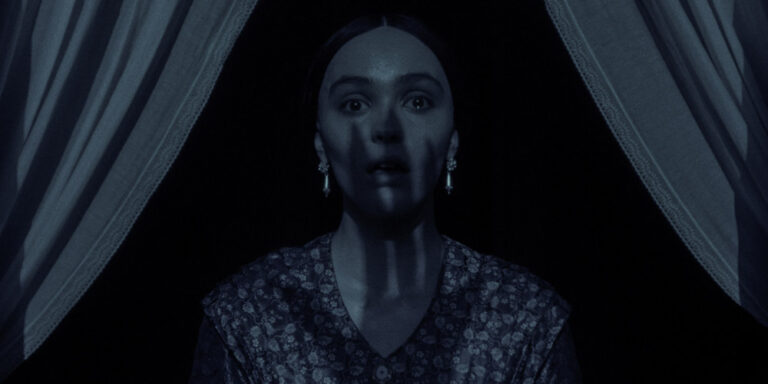

As in his poignant anti-biopic Spencer, Pablo Larrain takes many real aspects of Pinochet’s life and turns them into a kind of horror fable. Here Pinochet, as in real life, is accompanied by his wife, his butler and his children. The deliberately apocryphal hypothesis is that Pinochet never died in 2006 and lives as a 250-year-old vampire feeding on liquefied hearts. To think of Pinochet as Dracula is simply irresistible. The political ostracism in which he lives in some remote countryside location just like Dracula living in the most inhospitable parts of Transylvania, the military loyalty and obligingness of Fyodor his butler (Alfredo Castro) suggesting he is Renfield, the environmental expressionism and the stark monochrome photography all seem ripped out of a classic Universal horror film.

In essence, these factors embrace mythological ideals, always fostering an allegorical interpretation rather than a realistic one. Clearly, in terms of the dictator’s personality alone, certain liberties are taken that impregnate the film’s aims with ambiguity; basically, this supports the thesis I initially stated when I said that the film could be pilloried for its ambivalence. It is very likely that to enjoy the stylish and vulgar dialogues of this film you must have a rather self-conscious sense of humor and even a very idiosyncratic one. Larrain’s erotically arty filmmaking wants you to meditate on the moribund disgrace of the immortal Chilean dictator, yet he also unscrupulously wants you to laugh at that tragic paradox. That’s somewhat erratic filmmaking, but Larrain magnificently pulls it off. There was not a solitary minute of this breathtaking expressionist tableau that made me question the purity of its aesthetic density. Indeed, the aesthetic tools here are infallible, Edward Lachman’s portentous black and white cinematography shapes Larrain’s idiosyncratic mise-en-scène with enigmatic symmetry. You don’t watch El Conde, you savor it.

Like all villains, Pinochet is also an interesting figure as a fictional and real character, but even with all his vampiric histrionics, the most intriguing character in this film is his antagonist, apparently Van Helsing in a female and religious version, Carmen (Paula Luchsinger). A nun who is hired by Pinochet’s rapacious heirs to exorcise and kill their father. When Pinochet meets this young, virginal nun posing as a financial auditor, he instantly falls in love with her carnal freshness and immaculate blood. His overbearing and deceitful wife Lucia Hiriart (Gloria Münchmeyer) enters into a melodramatic confrontation with her children and husband, and with Fyodor as well when this disruptive character alters the existentialist course of the Pinochet family. This is when the film displays its best dramatic attributes, both as a punchy dialectic and as a fierce tragicomedy. To mention that Carmen is the most intriguing character is curious since she somehow incorporates the ambivalent attitude of the film’s philosophy. This character has to pretend to be something she is not for the sake of her devotional mission, yet the erotic and subtly blasphemous power of Paula Luchsinger’s performance engulfs her character in a convoluted theology and intricate morality that ultimately proves to be the film’s greatest irony. Just as Carmen falls under Pinochet’s demagogic spell, in real life many were also seduced by his rhetoric.

There are extraordinary sequences where we see the vampire Pinochet soaring over the skies of large cities hunting for his next victims. The metaphor being that Pinochet’s terror is still prevalent in Chilean society, lurking out there waiting to be reincarnated in another new Pinochet to repeat the tragic history. The poetic structure of these metaphors here are unmistakable, whether they mirror a contemporary socio-political climate or not, Larrain’s percipient camera makes this political vampire a creepy myth but what is most chilling is how that myth is actually a mimesis of reality.